Vladimir Putin’s Recent Language Suggests War

February 20, 2022

James W. Pennebaker, Ryan L. Boyd, and Ashwini Ashokkumar

We’ve spent decades analyzing the way people’s language reflects their psychological states. One of the most revealing words is “I” (and me, my, and mine). Self-referencing (that is, “I-words”) often signals honesty and genuine openness with others. On the other hand, when trying to hide something or to actively deceive others, people tend to use I-words at lower levels.

It may be possible to detect Vladimir Putin’s motives about Ukraine by analyzing the ways he uses language in his press conferences. Using a new version of the text analysis program Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC-22), we have analyzed 21 press conferences and interviews Putin has given since 2004, with special attention to his meetings with the press since December 2021.

As can be seen in the graph, Putin’s five most recent meetings with the press since January stand out. Compared to his usual rate of I-words, his have dropped between 25–35% in his most recent press gatherings. At the same time, his use of risk-related words (threat, danger) and formal expressions of politeness (please, sorry, thank you – another sign of psychological distancing) have almost doubled compared to his numbers in previous years. Interestingly, he is also using words that express more certainty and confidence than in the past.

When we analyzed Putin’s language in December, we felt that Putin was not committed to any aggressive action in Ukraine. His word use had remained relatively stable for about five years. Given his language shifts over the last two months, however, we have changed our minds.

Our findings are in line with previous analyses of leaders preparing to launch an assault who understandably try to hide their intentions from their enemies. This was apparent with George W. Bush when he made the final decision to go to war against Iraq in 2003. In his weekly meetings with the press, his I-words dropped almost by half once he made the decision — this was reflected in his language six months before the war started.

It should be emphasized that drops in I-words can reflect many issues other than an intention to launch an invasion. That said, it’s hard to ignore this notable shift in Putin’s language when the stakes of his actions are so high.

To learn more about the methods and previous studies, check out the following sources.

Chung, C. K., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2011). Using computerized text analysis to assess threatening communications and actual behavior. In Chauvin, C. (Ed.), Threatening communications and behavior: Perspectives on the pursuit of public figures (pp.3-32). Washington, D. C.: The National Academies Press.

Pennebaker, J.W. (2011). Using computer analyses to identify language style and aggressive intent: The secret life of function words. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, 4, 92-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17467586.2011.627932

Pennebaker, J.W., Boyd, R.L. Booth, R.J., Ashokkumar, A., & Francis, M.E. (2022). Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, LIWC-22: A text analysis program. http://www.liwc.app

*For more information, contact Pennebaker at Pennebaker@mail.utexas.edu. He is Professor of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin

Optimism and Certainty in Trump and Biden’s Acceptance Speeches

September 19, 2020

Kayla N. Jordan, Ph.D

Harrisburg University of Science and Technology

With 45 days until the election, the time to understand the candidates is winnowing. In the last post, I explored the content of the two candidates’ nomination acceptance speeches and considered what that implied about their values and priorities. Rather than what they said, this post examines how they talked about different issues throughout their speech. For each segment, I track how positive and certain they were in the ideas they were communicating.

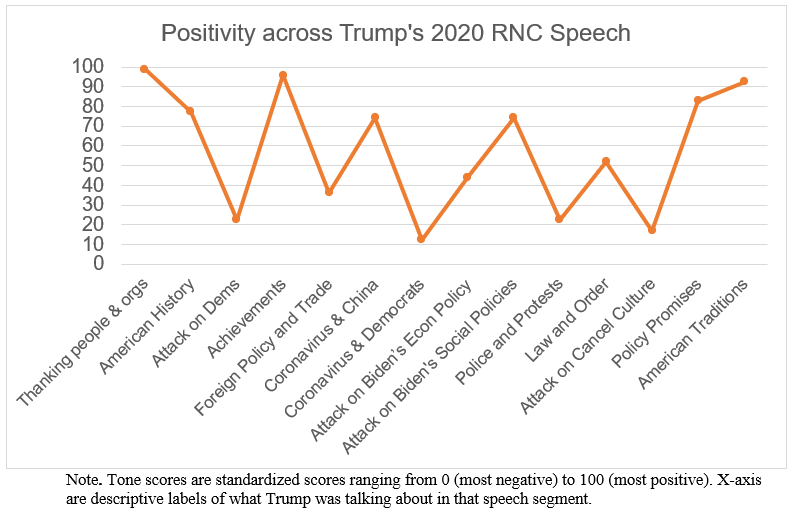

Before analyzing the two speeches with LIWC2015, they were segmented into 500-word chunks. As Trump talked longer, his speech was split into 14 segments where Biden’s shorter speech was split into 7 segments (with the last segment only ~200 words). The level of positivity (as measured by LIWC’s emotional tone metric) was measured in each segment revealing how optimistic (versus pessimistic) the candidate felt about that topic. Additionally, the level of certainty (as measured by LIWC’s cognitive processing dictionary) was measured in each segment revealing how much the candidate might have still been working through their ideas about that topic. The figure below shows changes in Trump’s positivity over the segments in his speech. The labels on the x-axis describe what he was talking about in each 500-word segment.

Throughout his speech, Trump bounced back and forth between high positivity and optimism and darker negativity and pessimism. Trump was most optimistic about his own achievements, promises, and ideas. However, after touting his own ideas about a topic, Trump often turned his attention to Biden and the Democrats. These attacks on the other side were when his speech was most negative and dark, forecasting doom and gloom in a Biden presidency.

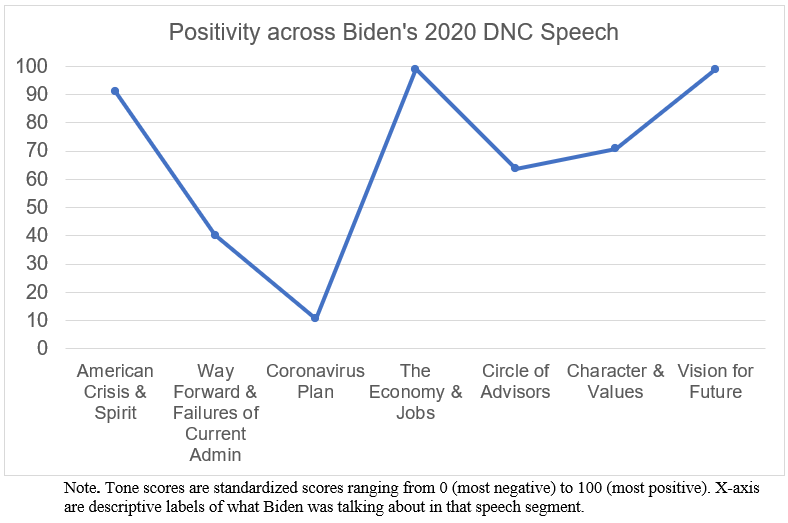

The figure below shows changes in positivity across Biden’s speech. Biden’s shorter speech contained fewer concrete policy discussions and more abstract discussions of American character. Biden’s speech began very positively with hope for the American spirit and future. His speech then turned darker addressing the current crisis and the failures of Trump’s administration to address the problems of the nation. His positivity then rebounds, first about his economic plan then ending his speech optimistically outlining the people, character, and vision he would bring to the office of the presidency.

In addition to varying positivity, Trump’s speech also varied in how certain he was about different topics. Certainty here is measured using LIWC’s cognitive processing dictionary where higher scores indicate less certainty. People using more cognitive processing words are still working through their ideas and solutions. Trump was most uncertain during three points in his speech: in the beginning when talking about great leaders in U.S. history, in the middle when discussing the pandemic and attacking Joe Biden and the Democrats, and in the end in his attack on ‘cancel culture.’ These points of uncertainty might point to where Trump is still figuring out his campaign strategy and his own policy ideas.

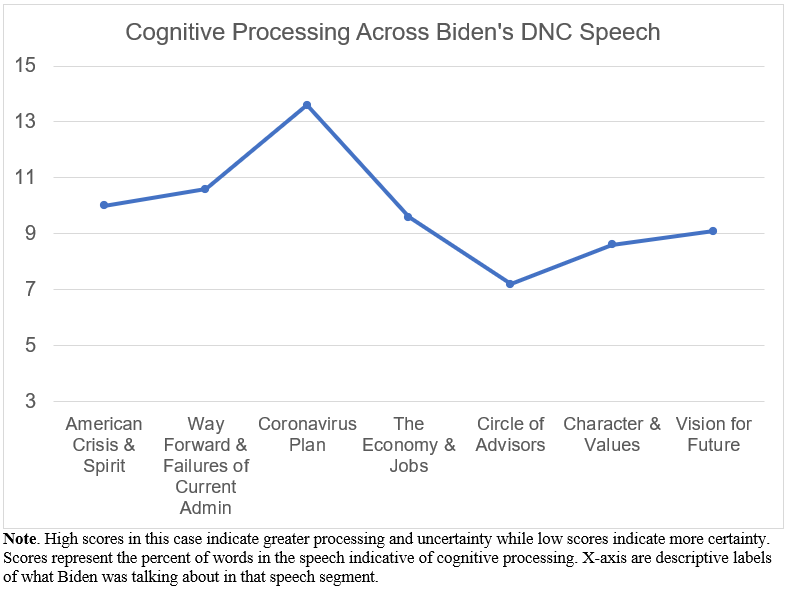

The figure below shows Joe Biden’s level of certainty through his speech which follows an S-shaped curve. Rising in the beginning, Biden was most uncertain about his coronavirus plan, likely still working through what would be the best response to a complex situation. He grew more certain as he continued, particularly when discussing his circle of advisors and the people and groups he would take advice and ideas from if elected.

The two presidential candidates are presenting very different visions for nation this election. Their nomination acceptance speeches not only focused on different policies and ideas, the candidates think and feel differently about them. Both candidates are generally optimistic about their own proposals and records while being pessimistic about their opponent’s ideas. The pandemic is a source of uncertainty for both candidates, but Trump seems more optimistic. While Trump painted a dark vision without him in the White House, Biden focused more on his own vision and more confidently projected a hopeful future. As the candidates continue their campaigns, the next posts will consider what we can learned from their interviews and town hall appearances.

Contact: kjordan@harrisburgu.edu

The Race is On: A Content Analysis of the 2020 Presidential Nomination Acceptance Speeches

September 9, 2020

Kayla N. Jordan, Ph.D.

Harrisburg University of Science and Technology

The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election is in full swing as the candidates, Donald Trump and Joe Biden, have officially been nominated by their parties. Although these two candidates are the oldest on record, they are quite different in both policy and personality. How might these differences (and potential similarities) be quantified? As they square off in the 2020 presidential election, I will be exploring many of linguistic features including thinking style, authenticity, and motivation. That said, in this first post, I analyze the content of their nomination acceptance speeches to explore the visions they have for the nation.

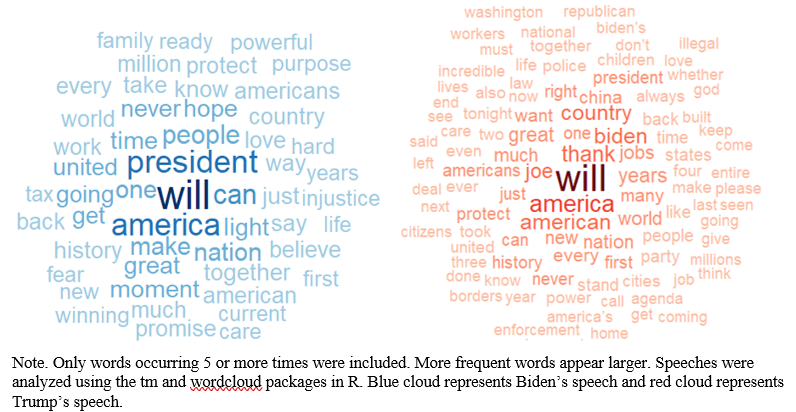

The figure below shows the words most frequently used by the two candidates, Biden in blue and Trump in red. General patriotic (e.g. great, America, people) and government (e.g. president, nation, country) words obviously featured in both speeches. However, two telling differences emerge. First, the candidates have different policy priorities. Biden’s speech was light on policy details but focused on work and family (e.g. work, back, promise, love). Trump’s extra-long speech hit many of his signature policies with a specific focus on law and order (e.g. police, illegal, enforcement, borders). Second, Trump was explicitly partisan using his opponent’s name 30 times and making the case for Republicans this election. Conversely, Biden never used his opponent’s name and did not explicitly evoke party politics (using the word democrat only once and never referring to republicans) keeping the focus on himself rather than his opponent.

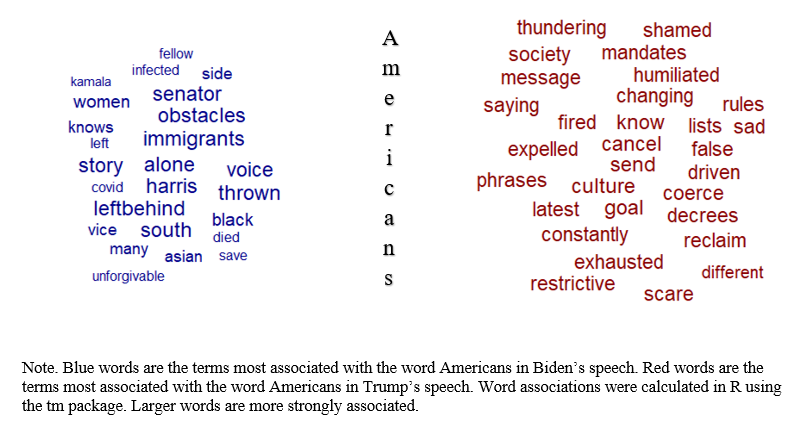

Though Trump and Biden used some of the same words, they did not always mean the same thing. To understand the different views Trump and Biden had on important concepts, I calculated which words in the speeches were most often associated with two terms: ‘Americans’ and ‘country’. In the figure below, the blue word cloud represent the words Biden used more often when talking about Americans and the red cloud are the words Trump used more often when referring to Americans. For Biden, the most important feature about Americans currently is how they have been impacted by the pandemic. For Trump, the view of Americans seems darker suggesting dangers to rights and liberties.

Both candidates also referenced ‘our country’ multiple times in their speech but based on the figure below (Biden in blue and Trump in red), they have different perceptions of the country. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a Democratic nominee, the top issues for the country in Biden’s view are health, education, and the environment. Furthermore, Biden focused on the nation’s ongoing problems with justice and inequality. True to his brand, Trump’s view of the country’s top issue was immigration. Rather than thinking about the country’s internal issues Trump was fixated on potential external threats.

While many posts on this blog focus on uncovering the psychological states and processes of the candidates, their language also reveals their perspectives and visions for the nation. In the nomination acceptance speeches, President Trump and former Vice President Biden presented wildly different views for the future. Biden’s vision focuses on American families and improving the lives with changes to health, education, and work. Trump’s vision focuses on tradition and protection seeing the way forward through the past and through freedom from interference. As they meet in debates and continue their campaigns, we will have more opportunities to learn about both the candidates themselves and their plans, but these two speeches provide a clear picture into the candidates’ perspectives on the nation. Check back in the next week for further analysis of the candidates’ acceptance speeches and other texts.

Contact me at kjordan@harrisburgu.edu. Thanks to Kate Blackburn for helpful comments.

Kayla N. Jordan, Ph.D.

Harrisburg University of Science and Technology

The parties’ conventions are now over. The candidates have accepted their parties’ nominations, and the general election has officially begun. In the coming weeks, we will learn more about the candidates in debates, stump speeches, and other events. Before that, it is worth looking at what we can glean about the candidates from their convention speeches. In this post, I explore the two vice presidential candidates: Senator Kamala Harris and Vice President Mike Pence. In a LIWC analysis of their speeches, two features stood out: their motivations and risk orientation.

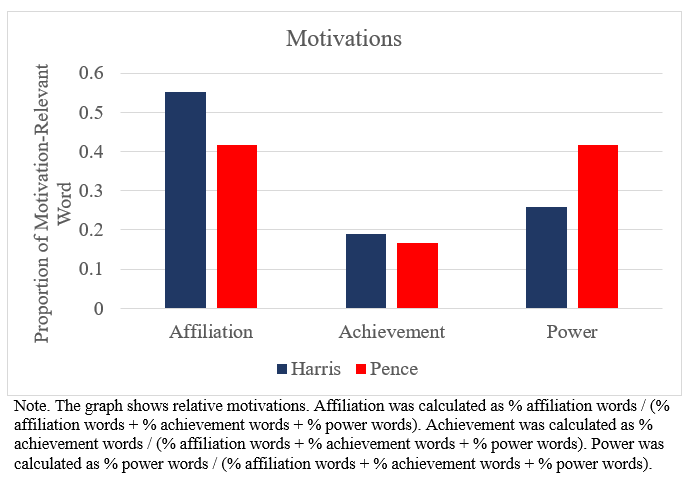

David McClelland’s motivation theory posits three major drives of human behavior: power, affiliation, and achievement. In studies of U.S. presidents, power motivated presidents (like FDR and LBJ) tend to be rated more effective by historians but are also more likely to enter a war. Affiliation motivated presidents are often good negotiators but can be weighed down by scandal (like George W. Bush and Nixon). Achievement motivated presidents (like Woodrow Wilson) can be highly idealistic but also ineffectual. Here I measure these motivations using LIWC2015 where power motivation is indicated by use of words like leader, demand, and strength, affiliation motivation by the use of words like help, family, and ally, and achievement motivation by words like win, excellence, and gain.

During the Democratic primary, Kamala Harris scored relatively high in power motivation and relatively low in affiliation motivation. As shown in the figure below, her nomination acceptance speech showed a different set of motives. Unlike in the primaries where she was vying against other Democrats and focused on status, the now Democratic nominee for vice president was mainly concerned with affiliation. In making the case for the Democratic ticket, she focused on family and community using both personal examples (e.g. ‘She taught us to put family first—the family you’re born into and the family you choose.’) and political ideals (e.g. ‘People of all ages and colors and creeds who are, yes, taking to the streets, and also persuading our family members, rallying our friends, organizing our neighbors, and getting out the vote.’). Senator Harris seems to now be motivated primarily by social relationships and bringing the Democratic party and nation together.

Mike Pence also showed affiliation motivation in his nomination acceptance speech with talk of his family (e.g. ‘would not be possible without the support of my family’) and the nation (e.g. ‘A country doesn’t get through such a time unless its people find the strength within.). However, Vice President Pence’s speech demonstrated an equally strong power motivation. Much of his speech focused on the strength of the president (e.g. ‘Donald Trump had leadership and the vision to make America great again’) and status of the nation (e.g. ‘if you want a president who falls silent when our heritage is demeaned or insulted, then he’s not your man.’). As his own status is being threatened, perhaps it is unsurprising that Pence’s speech showed motivation to keep that status and power.

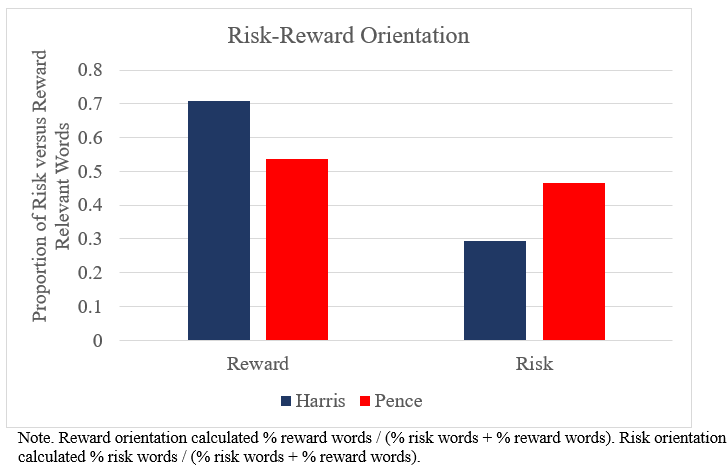

Beyond their motivations, the VP candidates differed in their risk orientation. Pulling from regulatory focus theory, some individuals are naturally more risk averse and cautious. They prioritize safety and security in their decision-making processes. Other individuals are more risk seeking and make bold choices. They prioritize rewards and benefits when making decisions. Linguistically, risk-oriented (or risk-averse) people tend to use words like danger, defend, and disadvantage. Reward-oriented people tend to use words like better, optimistic, and achieve.

In the Democratic primary, Harris tended to balance risk and reward concerns using words indicative of each equally. The figure below, which shows the relative use of risk versus reward language, indicates a slight shift in Harris’s orientation. In her acceptance speech, Harris was significantly more reward-oriented. Rather than focusing on dangers, Harris focused on the benefits that could come with a Biden-Harris administration (e.g. ‘not just to get us through our current crises, but to somewhere better’). Mike Pence, on the other hand, considered risks and rewards more equally in his speech. His speech outlined the accomplishments and goals of the Trump-Pence administration (e.g. ‘we have a President with the toughness, energy and resolve to see us through’). However, Pence also hammered home the risk and dangers of a Biden presidency (e.g. ‘Joe Biden would set America on a path of socialism and decline’). Beyond the rewards of another four years, Pence was preoccupied with the risk of an electoral loss.

Given the age of the presidential candidates this election year, the likelihood of the eventual vice president becoming president is potentially greater than normal. Hence, understanding how Senator Harris and Vice President Pence approach problems and decisions is especially important. As a vice presidential candidate, Senator Harris is focused on bringing people together and how to make the nation better. Vice President Pence is more split in his focus. On one hand, he also considers social relationships and progress, but he is equally focused on power (his own, the party’s, the nation’s) and the risks of the other side’s plans. Soon, the VP candidates will meet in their first and only debate providing another opportunity to glean insights into how they might approach governing.

Contact: kjordan@harrisburgu.edu

The First Ladies: A Quick Look at the Convention Speeches of Michelle Obama, Jill Biden, and Melania Trump

August 26, 2020

Kayla N. Jordan, Ph.D.

Harrisburg University of Science and Technology

Though not running for office themselves, the wives (and all too rarely husbands) of presidential candidates are visible figures both in the campaign and in the administration. The spouses of presidential candidates are usually not directly involved in politics themselves (the Clintons being a notable exception and why I’m not including Hillary Clinton here). Michelle Obama was lawyer and community organizer, Dr. Jill Biden a teacher and professor (until just recently), and Melania Trump a model. At the parties’ conventions, the goal of the candidate’s spouse generally is to humanize and soften the candidate with their speeches often containing less political content and more stories about and focus on the candidate as a person. In this post, I consider how these words these women used reflect their views of their spouses (or in Michelle Obama’s case someone she and her husband worked closely with).

Given the goal of humanizing the candidate, the convention speeches of the spouses are often filled with personal stories without the same structure and formality that other political figures bring to their speeches. Hence, one interesting linguistic dimension to consider is analytic thinking. Analytic thinking is a composite measure of function words (like articles, prepositions, and adverbs) that captures how someone is organizing their ideas. Those high in analytic thinking organize their thoughts more formally and hierarchically; they focus on ideas and concepts. Those low in analytic thinking organize their thoughts more informally and like a story; they focus on people and actions. Check out this paper to learn more about analytic thinking in politics.

The figure below shows how First Ladies Obama and Trump (and potential First Lady Biden) compare on this metric. In her most recent speeches, Michelle Obama stands out as being relatively low in analytic thinking. Her speeches focus on the stories of the American people and their experiences rarely relying on political abstractions or symbols. Dr. Jill Biden and Melania Trump are somewhat higher in analytic thinking. They both still weave in stories and anecdotes, but their speeches contain more formal, abstract language (e.g. “Yes, so many classrooms are quiet right now. The playgrounds are still. But if you listen closely, you can hear the sparks of change in the air.” [Jill Biden], “The common thread in all of these challenging situations is the unwavering resolve to help one another.” [Melania Trump]). While personal moments came through in their speeches, Dr. Biden and Melania Trump seems to have more trouble than Michelle Obama at creating a truly human, personal story.

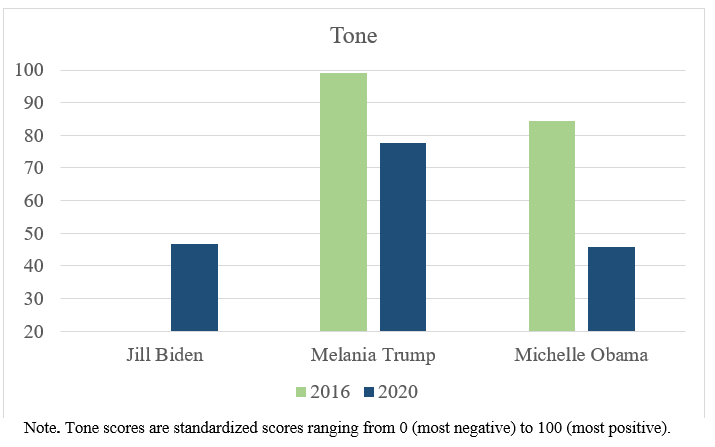

Potentially the single most important feature of political convention speeches is their tone. Like in previous posts, here I quantify tone using LIWC2015 which measures the difference in positive emotion words used and negative emotion words used. Across speakers at the Democratic convention (and likely the Republican convention), speeches have been more negative than normal given the current state of the nation. This same drop is seen in Michelle Obama and Melania Trump’s speeches compared to their 2016 convention speeches. Looking at just this year’s conventions however, Michelle Obama and Jill Biden were much more negative than Melania Trump. The Democratic women’s negativity is seen in their focus on the numerous challenges facing the country and the criticism of the current leadership.

Melania Trump, on the other hand, though using emotional words at similar rates, was exceedingly positive in her speech. With minor nods to the pandemic and racial injustice, her language was generally optimistic focused on opportunity and hope. That said, the words she used do not quite capture the full picture of her speech. For those who watched these speeches, the tone of Melania Trump’s words didn’t seem to match her nonverbal communication. Whereas Michelle Obama and Jill Biden used not only emotional words but also emotional facial expressions and intonation, Melania Trump’s words may have carried emotion, but her facial expressions and tone were rather flat. Watching her speech, one may come away with the perception that it was an unemotional speech rather than an optimistic one.

First ladies (or potential first ladies) likely do not impact voter’s perceptions of the candidates to a great extent. However, their words provide an interesting perspective on the candidates which might reinforce positive perceptions or mitigate negative ones. In this year’s conventions, Dr. Jill Biden and Melania Trump humanized their husbands to some extent but may have been a bit too abstract. While circumstances led one to an optimistic speech and the other to a more pessimistic one, both clearly believe their husband is up to the nation’s current challenge and the job of president. Check back in soon for a look at the vice presidential candidates as the RNC begins to wrap up.

Contact: kjordan@harrisburgu.edu

Kayla N. Jordan, Ph.D.

Harrisburg University of Science and Technology

While the Republican National Convention started this week, I want to look back at one speaker from the DNC last week and consider how the past and present of the Democratic party might be illuminated by one of their most popular figures. Making his fifth appearance at the Democratic National Convention, former President Barack Obama spoke eloquently in support of his former VP, Joe Biden. While the current unprecedented situation calls for an unprecedented speech, it is worth considering how President Obama has changed through his many DNC speeches. Here I consider three features of his language: optimism, self-focus, and certainty.

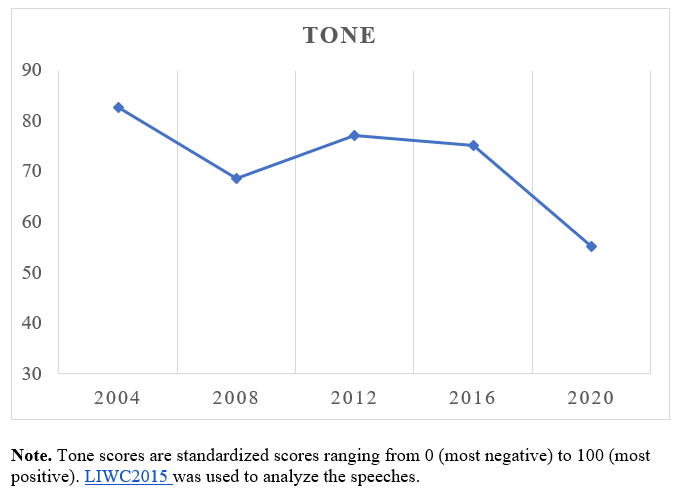

In his breakout speech, soon to be Senator Obama’s soaring rhetoric was filled with emotion and optimism. A linguistic analysis of the differences between the use of positive emotion words (happy, good) and negative emotion words (hate, kill) bears out this perception. As can be seen in the figure below, in his following speeches, he remained quite the optimist. His tone dipped a bit in his first nomination acceptance speech in 2008, but the nation was in a recession. While still on the positive side, Obama’s speech last week was the most negative he has ever given at the DNC. Likely this slightly darker tone reflects that not only is the economy once again doing poorly (like in ’08) but also there is a pandemic as well as existential threats to America’s democratic institutions.

Another interesting trend in President Obama’s DNC speeches is his declining use of I-words (e.g. I, me, mine, my). The use of the self-focused pronoun ‘I’ can be surprisingly informative. Psychological studies have found high use of I-words to be linked to greater honesty but also greater insecurity. Low use of I-words, on the other hand, is linked to greater self-confidence and security but also can come across as impersonal and distant. Obama used fewer I-words than any modern president and examining his DNC speeches reveals that he has used them less and less over time (in his DNC speeches at least). Already a self-confident individual, President Obama has become even more so as he has solidified his place in the Democratic party. While his elevated rhetoric may evoke distance, he spoke more authoritatively than ever in his support of this former vice president and his own legacy.

Finally, a surprising trend in President Obama’s speeches has been increasing uncertainty. Cognitive processing (indicated by words like think, believe, could, know) is a measure of how much a person is still working through an issue and trying to find a solution. Often, people who use fewer such words come across as very certain and unshakable in their beliefs. Since his first speeches in 2004, Obama has shown a nearly linear increase in cognitive processing. A plausible reason for his increasing uncertainty is increased complexity and unpredictability of his world, going from a young state legislator running for the Senate to presidential nominee to president to Democratic party leader. Given the election of Trump in 2016, Obama may still be working through how the nation has changed and the best way to reach the American people at this unprecedented time.

The changes in President Obama’s life (and the Democratic party to some extent) over the last decade and a half are reflected in his language. An optimist who, like all of us, has become a bit less optimistic in the current crisis, and a self-confident, experienced leader who realizes that simple answers may not always exist.

As we move into the Republican National Convention this week, it will be interesting to see how the leaders of the Republican party compare to Obama and the other Democratic leaders. Check back later this week for direct comparisons between Democratic and Republican figures during their conventions including Kamala Harris versus Mike Pence and Joe Biden versus Donald Trump.

Contact: kjordan@harrisburgu.edu

Kayla N. Jordan, Ph.D.

Harrisburg University of Science and Technology

This week saw the beginning of the 2020 Democratic National Convention with many notable political figures taking the (virtual) stage. One of these speakers was the trailblazing progressive, Senator Bernie Sanders. After another unsuccessful run at the presidency, Sen. Bernie Sanders once again gave a speech in support of someone he was recently in competition with. However, pundits have said that his speech demonstrated a stronger support of this year’s nominee, Vice President Joe Biden, than his support of 2016’s nominee, Hillary Clinton. Also, despite still not being a Democrat, Sanders seems to be more of a team player this election explicitly calling on his supporters to vote for Biden. Does his language support these perceptions? Short answer: yes.

Compared to his speech at the 2016 convention, Sanders’ speech this week was given with more certainty. In 2016, Sanders used more cognitive processing words (9.4% of his speech was words like should, believe, think). This week, only 7.6% of his speech was made up of these words indicating a greater sense of certainty in what he was saying. This certainty may be due to his desire to ensure supporters vote for Biden (instead of staying home or voting third party). He may also see Biden as a better ally than Clinton for advancing his progressive ideas.

His speech at the DNC also reflected a greater sense of affiliation with the Democratic party. When people are motivated by social relationships, they tend to use words like we, together, and ally. In 2016, affiliation terms made up 4.1% of his speech. This week, affiliation terms made up 5.7% of the words in his speech. Sanders may feel greater connection with Biden, and Sanders may also see the importance of coming together at this unprecedented time.

Two other changes in Sanders’ convention speeches are worth noting. First, while Sanders sincerely wanted Biden to succeed come November, his speech this convention may reflect some disappointment in his repeated failure to secure his own nomination. Sanders’ speech scored much lower on authenticity (dropping from a standard score of 22 to 11). To put party over ideology, Sanders may have felt the need to suppress his usual fiery, progressive style.

Second, this time Sanders was more confident in his own position within the Democratic party. Clout is a composite linguistic measure reflecting the status and power of the speaker. Sanders’ clout score increased from 2016 (79.8) to 2020 (89.2) suggesting that Sanders thinks he is in a better place within the Democratic party than he was four years ago. Check out these older posts for more info on how authenticity and clout are measured.

Once seen as a staunch Independent, Bernie Sanders has become a vital progressive figure in Democratic politics. As the progressive wing of the party grows, Sanders can provide a clue as to how progressive leaders and voters are viewing this election and Biden’s candidacy. The analysis here suggests that though they may not agree with all his positions, progressives see a Biden presidency as the only way forward at this juncture. Check back for more psychological text analyses of the 2020 Democratic and Republican national conventions as they unfold these next two weeks.

Contact: kjordan@harrisburgu.edu

Late Bloomer: A Look at Michael Bloomberg in his First Two Debates

February 27, 2020

Kayla N. Jordan, UT Austin

Former New York City mayor, Michael Bloomberg, is a recent addition to the Democratic debate stage (and Democratic party). This week was only his second appearance in the debates as he is currently self-funding his campaign and made the decision to not run in the first four primary states. To begin to catch up with the analysis done on the other candidates, this post focuses on where Bloomberg stands on three important metrics covered in past posts: thinking style, clout, and authenticity.

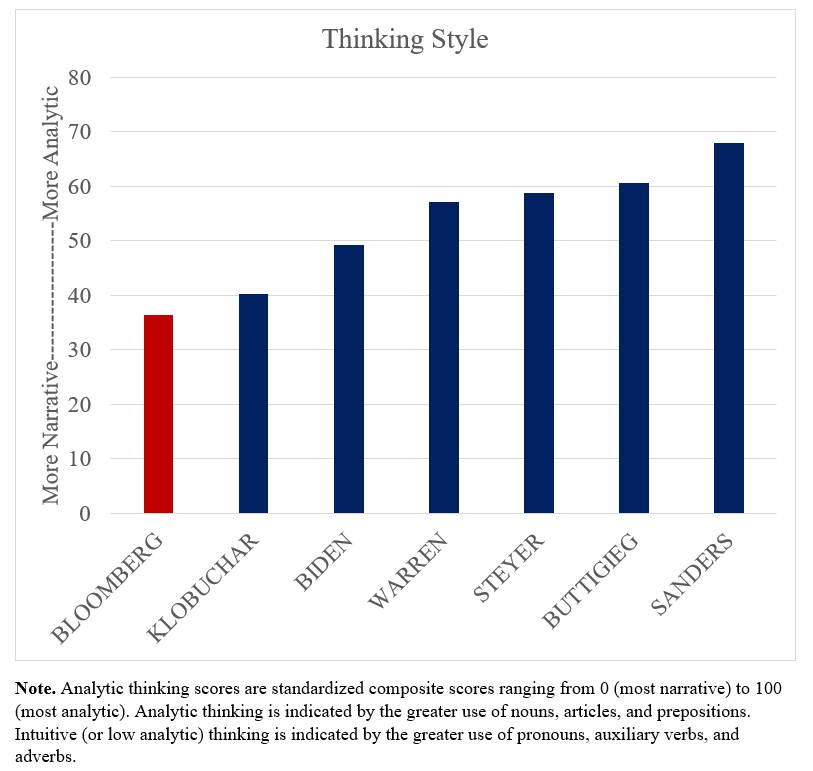

Thinking Style

In the very first post of this primary season, I discussed that the way candidates use words like pronouns, articles, and prepositions is a marker of analytic versus narrative thinking style. Some people naturally lean more toward an analytic, formal thinking style while others lean more toward an intuitive, informal style. From the data thus far, Bloomberg looks like the most informal of the bunch (though Klobuchar scores a close 2nd). His linguistic patterns are simple, intuitive, and not overly concerned with details and connections between ideas. There is little in the way of hierarchical, logical arguments. Rather, he focuses more on making statements and detailing his record (e.g. “I’ve trained for this job for a long time and when I get it, I’m going to do something rather than just talk about it.”).

Clout

In another post, I examined the metric of clout (or confidence). Past work shows that people high in status or confident in their position tend to talk more about others while those low in status or lacking confidence talk more about themselves. With Buttigieg, Bloomberg is one of the least confident of the remaining candidates potentially due to his newness to the national Democratic party establishment. Bloomberg is often defensive or tentative in staking his place on the stage (e.g. “I don’t remember what they were, so I assume if it bothered them, I was wrong, and I apologize.”, “I’ve met with Black leaders to try to get an understanding of how I can better position myself”).

Authenticity

In the first post of the season, I also analyzed the candidates’ authenticity. We know from past work that when people are being honest and straightforward, they tend to talk more about themselves and their present circumstances. Politicians are often not the most authentic or honest individuals, so the differences between them can be interesting. Once again, Bloomberg stands out as the most authentic candidate (with Buttigieg a close second). For example, while his answers may not satisfy his opponents or Democratic voters, he didn’t evade questions of his past behavior (e.g. “We let it get out of control. And when I realized that I cut it back by 95%. And I’ve apologized and asked for forgiveness”, “But right now, I’m sorry if she heard what she thought she heard or whatever happened. I didn’t take any pleasure in that.”).

An Interesting Comparison

Taken together, Bloomberg’s linguistic style is quite like one former primary candidate: Donald Trump. Like Bloomberg, Trump during the 2016 Republican primary debates had a very informal thinking style, was lower in clout than his opponents, and came across as highly authentic (for a politician). Beyond their shared business background and alleged past improprieties, Bloomberg and Trump seem to share a similar style of thinking about and communicating ideas. While Bloomberg might not win the Democratic nomination, his similarity to Trump makes him an interesting figure in the process.

Contact: kaylajordan@utexas.edu

Feel the Bern: Emotion and Social Focus in the Nevada Democratic Debate

February 20, 2020

Kayla N. Jordan, UT Austin

In the Las Vegas debate ahead of the Nevada caucus, the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates clashed in arguably the most heated debate so far. Michael Bloomberg, a late comer to the 2020 primary and the Democratic party, hit the debate stage for the first time. Joe Biden struggled with disappointing finishes in Iowa and New Hampshire while Warren, Buttigieg, and Klobuchar fought to unseat Sanders as the new front-runner. Amidst these complex dynamics, the candidates lost much of their usual congeniality attacking each other on both policy and personality.

While I usually analyze the candidates across debates, here I want to focus solely on this most recent debate. Rather than say something about the traits of the candidates, this post will consider how the candidates are reacting and interacting to each other and the ups-and-downs of the primary process. To capture the fieriness of the last debate, I examine the extent to which the candidates used positive and negative emotion. To capture the recent contentiousness of the primaries, I analyze how socially focused the candidates were as a proxy for how much the candidates may value (or not value) unity and teamwork.

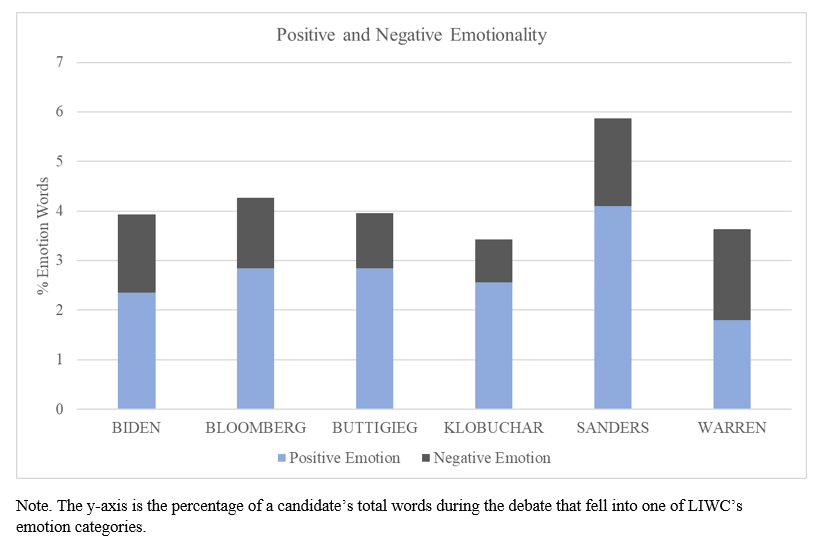

Emotionality

Many methods have been devised to measure emotion from language. Here I keep with the method used in previous posts and use the positive and negative emotion dictionaries from LIWC2015. Positive emotionality is measured by words such as excellent, benefit, and respect (620 words in the dictionary). Negative emotionality is indicated by words such as fault, doubt, and unsuccessful (744 words in the dictionary). The graph below shows the percentage of each candidate’s total words that fell into one of these categories, and there are three main points of interest.

1. The least emotional candidates were Warren and Klobuchar which bucks the traditional stereotype of women being more emotional than men. Linguistically, the female candidates kept their cool last night more than their male counterparts.

2. Despite being the target of several attacks, the most positive candidate was Bernie Sanders. Klobuchar and Buttigieg were also on the more positive side. All three of these candidates used over twice as many positive emotion words versus negative emotion words. Despite defending against and instigating attacks, these candidates talked more about their own positive qualities and not just about the opponent’s bad ones.

3. Warren was the only candidate to use more negative (versus positive) emotion words. Leading off the night with attacks on Bloomberg’s record on women, Warren did not hesitate to call out issues with other candidates’ past actions or policy proposals. What is interesting is that while she spent the most time on the attack, Warren was not overly emotional in her attacks. Overall, she used the fewest emotion-laden words, and generally came across as pointing out her opponent’s weaknesses in a relatively matter-of-fact manner.

Social Focus

Like emotion, the extent to which people are concerned with their social relationships can be illuminated by the words they use. With LIWC2015, social concern is measured by words such as help, talk, friend, and colleague (756 words in dictionary). Despite the general combative mood in the debate, candidates did differ in how socially focused they were and fell in three groups.

1. Warren and Biden used the most social words of the six candidates. Despite any animosity between the candidates, Warren and Biden both spent time focusing on how they need to work together to accomplish the goals they all agree on (e.g. ‘we have to change the tax code’, ‘We need to make an investment to level the playing field.’).

2. Sanders and Bloomberg were in the middle somewhat socially focused but generally focused more on conflicts between them. This can be seen in some of the interactions they had with each other. After agreeing that the rich needed to pay more tax, they devolved into personal attacks against each other (e.g. ‘the best known socialist in the country happens to be a millionaire with three houses’, ‘maybe we should also ask how Mayor Bloomberg in 2004 supported George W. Bush for president”).

3. Klobuchar and Buttigieg used the fewest social words. Rather than unity and shared goals, they tended to focus more on why they themselves were voters’ best option. This can be seen in the extended back and forth they had pointing out each other’s flaws (e.g. “You have been unusual among Democrats”, “Are you trying to say that I’m dumb? Are you mocking me here, Pete?”).

Looking Forward

Unlike past primary election cycles, the outcome of the Democratic primary is far from clear, and the probability of no candidate securing the nomination is unusually high. With so many candidates still in the race and the relatively high agreement between them on many issues, determining what does separate the candidates, like their communication styles and psychological traits, is potentially more important than ever. The analysis in this post demonstrates that one way the candidates differ is in how they handle conflict. It is hard to say which style would make the best candidate or best president, but hopefully the analysis can help voters determine which candidate might best match their ideal leader.

Contact: kaylajordan@utexas.edu

A Comparison of Trump and Clinton’s SOTU Addresses after Impeachment

February 5, 2020

Kayla N. Jordan, UT Austin

While I have been focused on the Democratic candidates lately, this seemed like a good time to check in on the (presumptive) Republican candidate, Donald Trump. This week Donald Trump became the second president in modern history to give a State of the Union (SOTU) address during an impeachment trial. Unlike Bill Clinton, however, Trump is facing reelection. In this post, I analyzed Trump’s recent SOTU address compared to his first three as well as Bill Clinton’s at the time of his impeachment. Beyond exploring possible psychological impacts of impeachment, the analysis gives a peek into the mindset of Donald Trump as he gears up for his reelection bid.

In facing potential removal from office, two linguistic measures are potentially interesting: emotional tone and I-words. As discussed in previous posts, emotional tone gives a sense of a person’s general outlook by comparing their use of positive emotion words (e.g. happy, respect, love) to their use of negative emotion words (e.g. anger, hate, death). People high in emotional tone come across as upbeat and optimistic while those low in emotional tone seem pessimistic and dark. Presidents facing impeachment might be expected to become more pessimistic given their circumstances.

The use of I-words (e.g. I, my) can be a bit of a double-edged sword. On one hand, greater use of I-words is associated with honesty and authenticity. On the other hand, greater use of I-words is also associated with depression and insecurity. In their SOTU addresses, presidents, particularly those being impeachment, likely want to sound as honest and sincere as possible, but may at the same time be conveying a sense of insecurity. So what can we learn from Trump’s (and Clinton’s) SOTU addresses?

The graph below shows how Trump’s tone has shifted across his four SOTU addresses. For comparison, Clinton’s first SOTU address after he was impeached by the House as well as his three preceding SOTU addresses are included. Both Trump and Clinton show a similar pattern across their addresses with a decreasing positivity over time and an increased optimism in the SOTU address following their impeachment. A couple of possible explanations exist for this counter-intuitive optimism. First, both Clinton and Trump may have simply been optimistic about their chances of surviving the impeachment process. The second explanation is strategy; even in the face of the vote against them, they believed they were still good for the country and wanted to remind people of the positive things they’ve done (e.g. “our economy is the best it has ever been”) and plan to do (e.g. “making sure that every young American gets a great education”).

Similar patterns are also found in Trump and Clinton’s use of I-words. For both presidents, I-words increase in the SOTU address following their impeachment. Both presidents are generally thought of as ‘authentic’, but the increase in I-words after their impeachments could further signal insecurity and a lack of confidence following the Congressional rebuke. While never directly mentioning the impeachment processes, both presidents made sure to highlight their contributions and goals (e.g. “I will send to Congress a plan… [Clinton]”, “I moved rapidly to revive the U.S. economy… [Trump]”). Such a self-focus may reflect a need to bolster their confidence after being hit with impeachment.

Despite showing similar patterns in their responses to impeachment, Trump is in a unique position. Like Clinton, he is very, very unlikely to actually be removed from office. However, even if acquitted, Trump faces re-election, so it is interesting to consider how impeachment may impact his campaign style. In the 2016 election, he was relatively optimistic in the primaries, but much darker and more pessimistic in the general election. Consistent with his latest address, he tended to use I-words at high rates. So on the campaign trail, we will likely see a return of the authentic (but perhaps insecure) Trump, but will the sense of optimism he brought to the SOTU remain or will he return to the doom-and-gloom candidate of the 2016 general election?

Contact: kaylajordan@utexas.edu